Retirees, even semi-retirees haunt libraries. I spent much of the first day after my return from Puerto Rico in the Roslindale branch of the Boston Public Library.

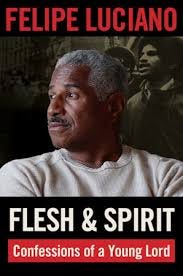

As if by magic, the very first book I put my hand on was one entitled “Flesh & Spirit: Confessions of a Young Lord,” by Felipe Luciano. With Puerto Rico on my mind, the book caught my attention and did not let go.

What follows here is a reflection on Luciano’s book, unencumbered by any knowledge of the Young Lords outside of what the book offers. Those interested in what Luciano calls a “definitive history” should consult “The Young Lords: A Radical History” by Dr. Johanna Fernández.

Puerto Rican migration to New York began in the mid-19th century but grew slowly until after World War II. In the 20 years between the end of the war and the mid-1960s, New York’s Puerto Rican population grew from 70,000 to 900,000. A majority of these migrants lived under very difficult circumstances in a relatively small area of East Harlem know as El Barrio.

In response to the social and economic circumstances of El Barrio’s Puerto Ricans and the constant police repression faced by the community, a small group of activists founded the New York Young Lords Party in 1969. Multiple East Harlem street gangs were one response to the situation. The Lords offered something else—a disciplined, principled organization with revolutionary ambitions. They demanded independence for Puerto Rico, but in the beginning their focus was revolutionary community organizing in East Harlem and, eventually, The Bronx.

Luciano was a founder of the local Lords and served as its first chairman. Barely two action-packed years later, he was out of the party entirely. For over a half-century he has wanted and needed to tell his side of the story.

Of special interest to me is why, after fifty years, Felipe could find the will and the energy to tell a story that some would say he might better have left alone. We don’t know how long Luciano spent writing this book, but he was well into his seventies when it was published. I expect at least a few people asked him “How’s retirement?” as his sweat, blood, and tears mingled on these pages.

The author offers his explanation of why he needed to write this book in his short introduction.

The past, old patterns of thought and behavior, began to affect my spirit, began to affect my relationships with my children, women, friends, and family. Metamorphosis of spirit had not occurred...Personal truth was to be chained and restrained because there were those who would take even a sliver of confession to discredit you. So, I began to write “The Book.”

Luciano is a fine writer. Since he’s an accomplished poet, it is no surprise that the language is often poetic. As a story, the text leaves the reader hanging in places, but an autobiography is not a story that one can expect to tie up each loose end that doesn’t involve the subject.

Along the way, Luciano must have revisited the question of why he was alive to write the book at all. He recalls several moments when he certainly should have ended up without breath. No cat has had more lives. He was the young, gifted, Black Puerto Rican gang banger who could talk or fight his way out of anything. But even in autobiography, every charm has its limits.

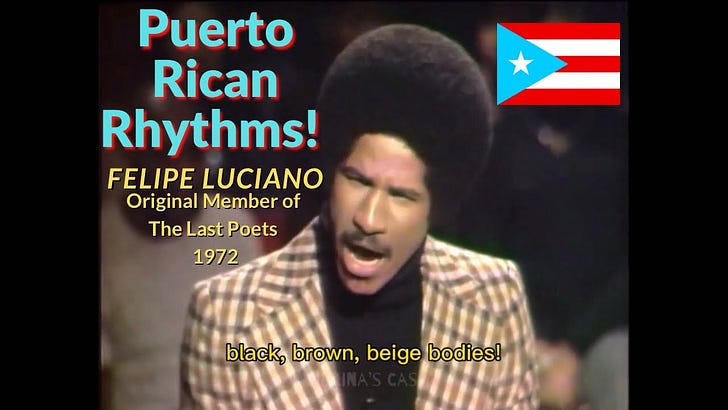

At age 16, Felipe and friends chased down Larry, a rival gang member who had beaten up Felipe’s brother. Luciano was right there when one of his boys plunged a knife between Larry’s ribs. The rival was gone, and Felipe was on a path that could lead only to incarceration and, ultimately, his own death. But his impressive wits and that lucky charm led him out of prison to Queens College, The Last Poets, La sociedad Albizu Campos, and ultimately to a group of young Puerto Ricans ready to make history. Through it all, he was acutely aware of being both Black and Puerto Rican, with all that implied for his vision of liberation politics.

We can see why the comrades made Luciano their first leader. He was a brilliant, committed revolutionary, a tough guy, and a master tactician. Perhaps most importantly, he had deep roots in the neighborhood. Among the founders, only one member besides Felipe came from El Barrio. He knew everyone and their mothers. Mothers were sacred.

At one point, Felipe suggests that the FBI had to kill Black Panther leader Fred Hampton because he possessed a rare genius for turning Chicago’s most irretrievable gangsters into revolutionaries. The Lords’ leader possessed a version of Hampton’s genius, one more reason that he is lucky to be alive to tell the story. The FBI’s infiltration of the Lords is not Luciano’s focus here, but the fingerprints of state repression are all over the story.

Luciano feared nothing and no one and was uniquely capable of inspiring confidence and action in others. Even in his telling of his heyday with the Lords, however, at least one Achilles heel is painfully apparent.

The tale gets a little dicey here. Felipe fell in love with and married a highly respected member of the party. In describing his pre-Lords life, he is very honest about his sexual promiscuity and his nonexistent sense of male responsibility for birth control during sex. Luciano acknowledges these as personal failings, expressing some remorse. He is careful not to say if this behavior continued after he became a revolutionary, married, and assumed a leadership position with the Lords. If it did, he was neither the first, nor the last.

What is clear is that Luciano believed in, and still recognizes a notion of “Revolutionary Machismo,” a re-framing of traditional masculinity as Luciano had experienced it. This idea was included in the Lords’ 13-Point Program. He insists that that this notion of revolutionary masculinity was critical to his ability to recruit gang members, drug users, petty criminals, and other community people to his organization.

Our author doesn’t say if occasionally asserting sexual power over women was part of this re-framed masculinity, but in any case not everyone in the leadership agreed with him on the possibility of a revolutionary machismo. These disagreements became critical when Luciano and the Lords faced a moment of truth.

That moment came when two White women approached Luciano, asking for advice about setting up an event. You know where this is going. He pleas entrapment at the hands of a government agent. Agent or not, his actions, witnessed by a fellow Lord, lead to an abrupt and irreversible change in Luciano’s personal life and his relationship to the Lords.

He acknowledges a terrible and utterly stupid mistake, one that a revolutionary leader cannot make. I sense, however, that he still believes that someone who had contributed so much to the movement deserved a better outcome, both in the Lords and in his marriage…a second chance. Fifty years later, his resentment at the fact that there was no second chance and that no one in the leadership stood up for him leaps off the pages of his book.

The Young Lords leadership saw the situation differently than Felipe. For them, “revolutionary machismo” was an oxymoron, at least as practiced by their leader. They demoted Chairman Felipe to the rank of cadre. Adding insult to injury, as he sees it, they named a woman in his place. He insists that this left much of their male base “rudderless.”

On the home front, his wife insisted that he move out after the incident and never expressed interest in reconciliation. At a second moment of truth, Felipe recounts that he came within a whisker of murdering the comrade who became Iris’s new lover. Shivers move up and down the reader’s spine before the charm returns, just in time.

Felipe Luciano was still a young man when he left the Young Lords. He has gone on to accomplish a great deal as a poet, a journalist, a teacher, and a recognized expert on the role of Latin music in the survival and flourishing of Latin American culture in the U.S. He is an example of the extraordinary accomplishments of the Puerto Rican diaspora, especially its Nuyorican variant, but through it all, aspects of his past have continued to trouble him.

Luciano never says if completing the book achieved the elusive “metamorphosis of the spirit.” Perhaps it was too soon for him to know. Whether or not he was successful in that quest, he has put his tercera edad to good use in shining bright light on an important chapter in the Puerto Rican experience in the United States. Others who would make change anywhere can learn much from the remarkable, the inspiring, and the troubling exploits of Felipe Luciano.

Thanks! I did not know about Luciano, the Young Lords, or this book. Now I know a little! Love the fact that it called out to you right after you got back from Puerto Rico. Keep writing!